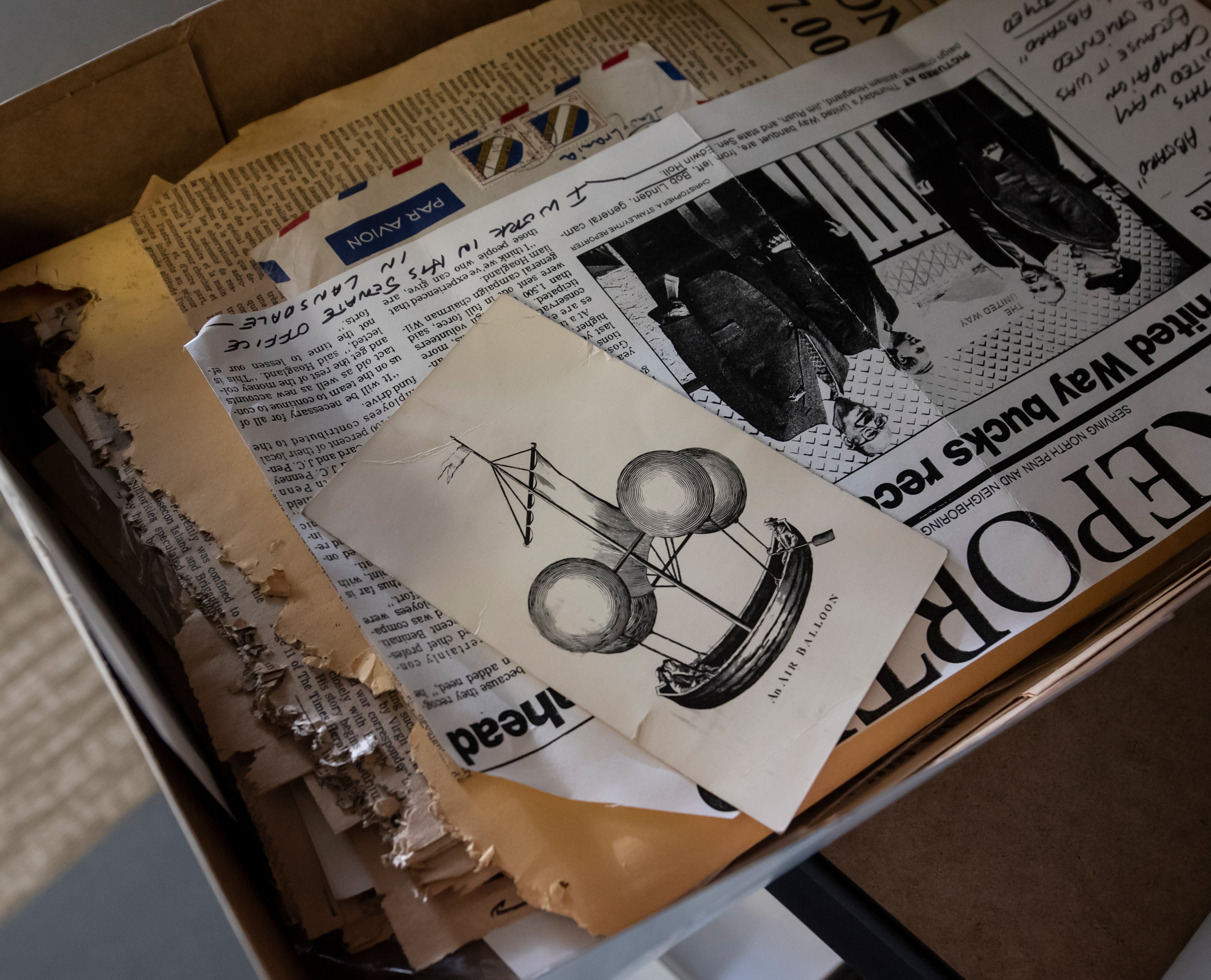

Decaying cardboard boxes, some half-eaten by mice, are stacked in the back of Jeanne Marie Laskas’s red pickup truck. She has just parked in front of the Cathedral of Learning and is yanking blue tarps from her mountain of cargo. Students, walking to or from class, stare as they pass. Laskas realizes she looks more like Elly May Clampett from The Beverly Hillbillies than an acclaimed writer transporting what amounts to another woman’s life story.

She calls to her research assistant, Rachel Wilkinson, who is waiting on the curb with a dolly. Wilkinson gasps at the heaps of boxes—almost 70 in all.

“I know! I know!” says Laskas, a distinguished professor of English in the University of Pittsburgh’s Writing Program and the founder of Pitt’s Center for Creativity. “It’s a lot. Let’s just go inside and see what we have.”

Wilkinson (A&S ’15G) loves digging into research with Laskas, her writing mentor. She’s helped the author investigate stories for national magazines and a New York Times best-selling book, Concussion, which chronicles the explosive discovery of a neurodegenerative disorder associated with repeated head injuries. (It was later made into a movie starring Will Smith.) She’s game for another big project, this time about the life of Constance Wolf, a spitfire of a woman known to Laskas as The Balloon Lady.

As they unload the boxes into a room on the Cathedral’s fourth floor, Wilkinson peeks inside what they’re schlepping. It’s not pretty. She sees dead stinkbugs and mouse droppings mingled with Wolf’s letters, photos, and memorabilia. Combing through archives, interviewing sources, fact-checking, reading and responding to article drafts—she’s used to plunging elbow deep into work with Laskas for a story. But this is asking her to get her hands dirty literally and figuratively.

“What did I get myself into?” Wilkinson asks, only half-joking.

Turns out, it’s another great writing adventure.

Sometimes, a good story comes to a writer with a sense of urgency. The work moves swiftly; it pours from the pen (or keyboard). Other times, a good story needs time to percolate.

In the three years since unloading the Balloon Lady archives with Wilkinson, Laskas has bounced on to other story projects, including articles in the New York Times Magazine and GQ and yet another critically acclaimed book. Like Laskas’s previous publications, they are all works of narrative nonfiction, a genre that uses literary storytelling techniques to tell highly researched and carefully reported true stories.

But the author hasn’t done this work alone.

Much of the writing takes root about 20 miles south of Pittsburgh, in a little blue house purchased in 2016 by Laskas to serve as a kind of retreat—a hub for her own work and for the writers who assist her. That’s where the Balloon Lady’s archives were relocated and carefully unpacked and sorted. It’s also where podcasts are recorded, story structures are sketched out, and quiet hours writing are interspersed with discussions about craft.

Laskas (A&S ’85G) has created the journalistic equivalent of a scientist’s research laboratory. Wilkinson and an informal collective of graduate students and alumni from Pitt’s Writing Program help her with big creative projects, gaining mentorship and professional experience along the way. Instead of test tubes and microscopes, their tools are laptops, audio recorders, archive boxes, pencils, and notebooks. The focus of their investigations: how to expertly tell true stories and share them with the world.

Laskas (A&S ’85G) has created the journalistic equivalent of a scientist’s research laboratory. Wilkinson and an informal collective of graduate students and alumni from Pitt’s Writing Program help her with big creative projects, gaining mentorship and professional experience along the way. Instead of test tubes and microscopes, their tools are laptops, audio recorders, archive boxes, pencils, and notebooks. The focus of their investigations: how to expertly tell true stories and share them with the world.

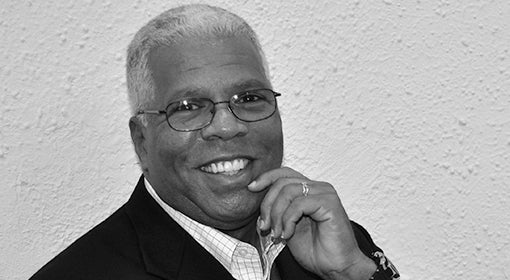

“It’s a story lab,” says Tim Maddocks (A&S ’15G), who first met Laskas when he was a Pitt graduate student studying nonfiction writing. After he earned a master’s degree, Laskas hired him to assist with some reporting and research. Now a working writer and a lecturer in the English department, he still occasionally pitches in on his mentor’s projects as he develops his own.

Writing is often lonely work, and the path to publishing can feel bewildering, especially for up-and-comers. But to work with Laskas is to see the doors to the creative process thrown open. A solitary endeavor becomes communal.

She meets with a group of mentees once or twice a week in the blue house to talk about their work and to offer support. Laskas shares ideas, tips, and publishing contacts.

But she doesn’t do all the talking. In the dining room, with its homey wood paneling and leaf-patterned curtains, she and the others gather around a table to laugh, recap recent interviews, and flesh out story ideas. It’s not unlike taking a writing class with Laskas, only the curriculum is self-directed, the lessons spontaneous.

The creative collaboration that springs up in the story lab has already made it onto the pages of some of the country’s most revered publications.

In 2016, not long after the team unpacked The Balloon Lady’s archives, Laskas’s curiosity did what Wilkinson has come to expect of her creatively energetic mentor. It veered in a different direction, toward another fascinating story.

The Pitt professor learned about the Office of Presidential Correspondence, a curious and hidden part of the White House in Washington, D.C. There, staff and volunteers combed through tens of thousands of letters every day and handpicked 10 for then-president Barack Obama to read and reply to each evening. Her writer’s eye focused.

What’s it like to spend your days reading letters to the president? she wondered. What even compels people to write to him—and what does it feel like to get a response?

She went to work to answer those questions. Wilkinson and, later, a number of other Pitt-connected people would play a crucial role in capturing the story.

At first, it wasn’t clear what it would look like, but the more they dug in, the clearer the picture got. While Laskas spent time in the mail room with staff and volunteers digging through piles of letters, Wilkinson tracked down the people who took the time to write to the president, some in admiration, others in anger or frustration. Having seen Laskas in action, Wilkinson knew how to get her subjects to open up and how to capture subtle character details as they relayed their emotional journeys to her.

At first, it wasn’t clear what it would look like, but the more they dug in, the clearer the picture got. While Laskas spent time in the mail room with staff and volunteers digging through piles of letters, Wilkinson tracked down the people who took the time to write to the president, some in admiration, others in anger or frustration. Having seen Laskas in action, Wilkinson knew how to get her subjects to open up and how to capture subtle character details as they relayed their emotional journeys to her.

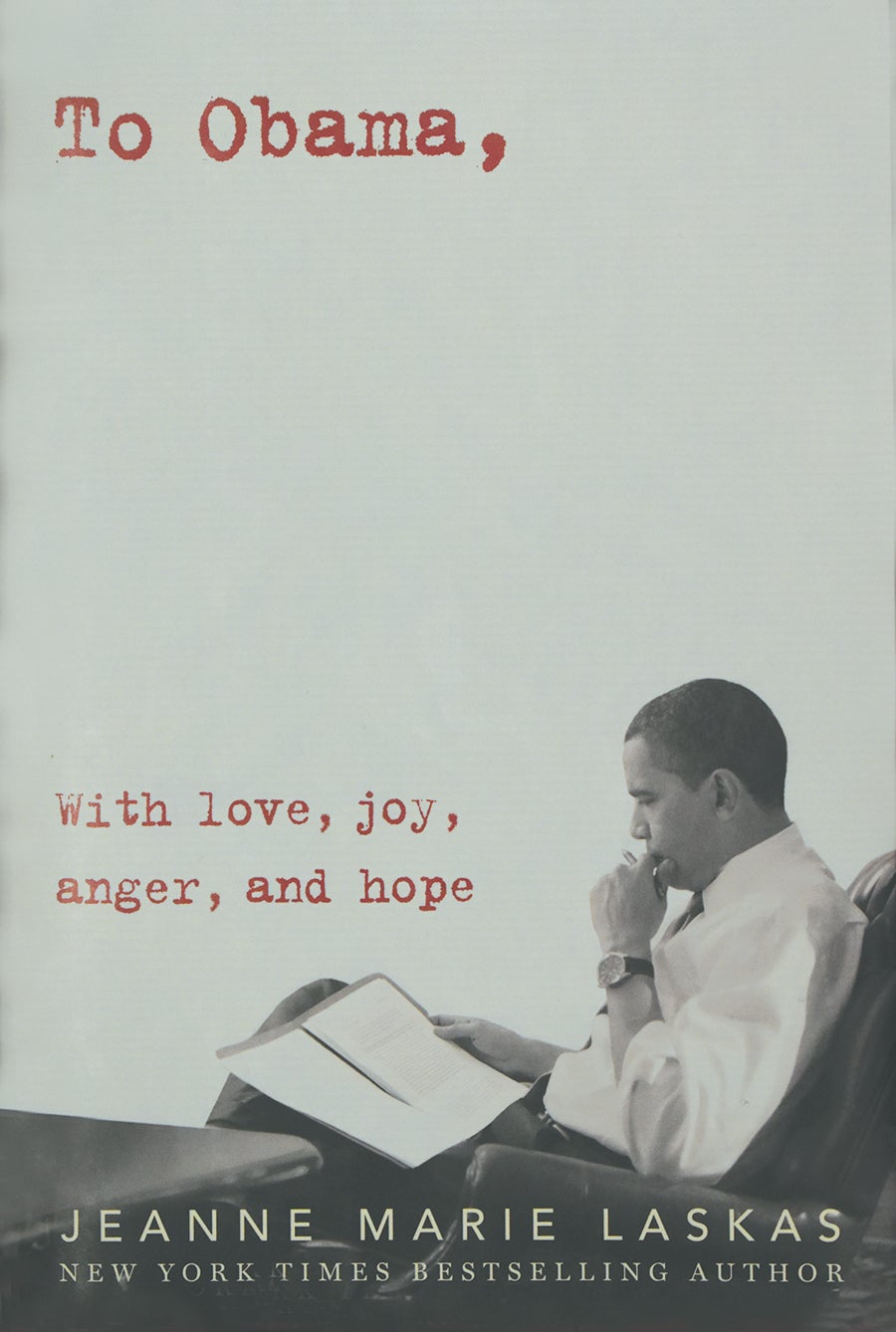

In January 2017, Laskas’s article on the White House mail room appeared in the New York Times Magazine and quickly went viral online. It was later named a finalist for the prestigious National Magazine Awards. Obama even wrote in a note to Laskas that it was his favorite story ever written about his administration. Before long, plans were in the works to expand it into a book.

Creative sparks flew. Rachel Ann Brickner (A&S ’14G), then a Pitt writing graduate student, was brought in to help promote the book on social media by creating mini-narratives derived from the team’s reporting.

The collaboration wasn’t limited to the written word. While work was still unfolding on the magazine article, Erin Anderson (A&S ’14G), an assistant professor in the Writing Program who concentrates on audio storytelling, happened to overhear a recording of one of the president’s letter writers.

“That’s a great rich voice,” Anderson said. She asked to listen to others and became enthralled. They would be perfect for a podcast. With Laskas’s enthusiastic thumbs-up, Anderson set to creating a multi-part narrative podcast, or audio story, based on the Obama letters, traveling the country to record interviews with letter writers. She has since secured a collaborative agreement with a major Hollywood production company to produce a series under her lead scheduled to launch in 2020.

To Obama, With Love, Joy, Anger, and Hope debuted worldwide in 2018 to critical acclaim. Publishers Weekly described the book as “a sucker punch to the heart,” Glamour named it one of the best books of the year, and in the U.K., the Sunday Times called it “The real story of Obama’s America.” It would eventually be translated into seven different languages.

And it all came together with help from the story lab collaboration.

One piece of advice Laskas often shares over the dining room table in the little blue house is to trust the immersive process of narrative nonfiction. Don’t overplan. Just hang out with people and listen.

One piece of advice Laskas often shares over the dining room table in the little blue house is to trust the immersive process of narrative nonfiction. Don’t overplan. Just hang out with people and listen.

That’s exactly what she did 38 years ago when she arrived unannounced at Constance Wolf’s driveway in Blue Bell, Pa. As a 22-year-old graduate student in Pitt’s Writing Program, Laskas had heard about Wolf, a daring and glamorous adventurer known for her record-breaking feats flying hydrogen-filled balloons at a time when the sky was still largely dominated by men.

The Balloon Lady lived up to the hype as soon as Laskas laid eyes on her. The 77-year-old woman, wearing Army fatigues, pearls, and a veil across her face, was cutting her grass—going full throttle atop her giant red farm tractor.

Whoa. There’s a lot to work with here, thought the young writer.

Wolf asked her brusquely, “Why are you here?”

Laskas coerced from her an invitation to go inside, which led to the first of many conversations and a friendship that lasted more than a decade. Wolf’s sense of adventure inspired Laskas to embrace a style of reporting and storytelling that could be just as daring.

“Connie did adventure for adventure’s sake,” she says. “I just loved that.” The way the Balloon Lady lived her life became Laskas’s creed.

She wrote an essay about the fascinating woman but always imagined writing more. Just before Wolf died in 1994, she asked Laskas to take all of her mementos. They were stored in boxes that once held the champagne Wolf would give away to appease startled homeowners when her balloon landed in their yards.

The writer stored the boxes in her barn. When she decided to transport them to the Cathedral, and, more than two decades later, the blue house, they were, as Wilkinson can attest, in less-than-pristine condition.

The writer stored the boxes in her barn. When she decided to transport them to the Cathedral, and, more than two decades later, the blue house, they were, as Wilkinson can attest, in less-than-pristine condition.

But Wilkinson didn’t mind searching through the boxes. She suspected that the pieces of a great story lay within.

When Laskas first told her about Wolf, Wilkinson could relate to finding inspiration in a gutsy mentor. “For a lot of us, you are that person, Jeanne Marie,” she said.

Wilkinson didn’t see herself as a journalist when she entered Pitt’s Writing Program as a master’s student in 2012. She favored the more contemplative work of writing literary essays. But she got a different perspective when she was hired as Laskas’s research assistant in 2013 after meeting her through the program. At first, she transcribed interview recordings and helped with the Concussion research. But to Wilkinson’s surprise, Laskas kept asking for her opinion on stories.

“It’s great. You have two brains on a story,” says Laskas, who has long hired graduate students to help with her work. In turn, she gave Wilkinson the kind of advice she wished she’d had as a young writer stumbling around in the dark.

“I got to see her whole process,” Wilkinson says.

Buoyed by Laskas’s lessons, the collaborative support, and a Pitt master’s degree in nonfiction writing, Wilkinson is a well-published narrative nonfiction writer herself, with bylines appearing in the Atlantic, Harper’s Magazine, and Smithsonian.

Though the story lab is a largely informal postgraduate collective, it mirrors the ways faculty in Pitt’s Writing Program, as part of the Department of English, help students prepare for productive creative careers.

“Our primary aim is to make people better writers,” Director Peter Trachtenberg says. “Our secondary aim is to make people working writers.” That’s done, he says, both in and out of the classroom.

Recently, for example, the English department partnered with City of Asylum, a nonprofit focused on creative cross-cultural exchange, to build a class in which undergraduates write for and help to maintain the organization’s literary magazine, Sampsonia Way.

And Laskas leads a nonfiction and fiction writing graduate course that culminates in a trip to New York City, where students meet and discuss their work with editors and literary agents. Before that, the semester is spent learning, among other things, how to pitch stories to publications.

Mike Benoist, Laskas’s story editor at the New York Times Magazine, commends what she provides to burgeoning writers.

“It’s completely in her nature to be collaborative in writing and wanting other people to succeed,” he says. “Early on, it can be really difficult to have confidence in yourself and your writing. I am envious of her students that they found someone who took so much interest in them.”

When most of the team was working on To Obama, writer Tim Maddocks dug into the balloon world. He contacted the aging crowd who knew Wolf personally.

The connection led to Maddocks, Laskas, and Wilkinson descending on the 13th Annual Chester County Balloon Festival at 4 a.m. on a June day last summer. The three-day event included a special commemoration of Wolf and her pride and joy—a blue balloon embroidered with a picture of William Penn. Seeing the antique aircraft fill up brought life to all those dusty records.

One morning, when the wind was still, they watched two elderly men climb into a balloon and soar through the sky. The writers followed the balloonists, eventually finding them safely landed but tangled in a tree. The two men were utterly elated, saying their flight had gone according to plan, landing spot and all.

Back in the little blue house, the three recall the drama, laughing. It isn’t clear yet how, exactly, the book about Wolf will be shaped and if that scene will find a home there. But—like the tangled landing—it’s all going according to plan.

Cover image: Tim Maddocks and Rachel Wilkinson

This article appeared in the Winter 2020 edition of Pitt Magazine.