Pitt Magazine’s Winter 2018 issue features the story of Byong Kwon (GSPIA ’68), a Pitt alumnus and former South Korean diplomat who now runs Future Forest, an environmental nonprofit organization helping to green up China. (Read more here.)

Kwon was part of the first modern wave of South Korean students to pursue an education at the University of Pittsburgh. Many followed. Today, South Korea has a large and organized Pitt alumni base. Its members include leaders in education, technology, government, the private sector, nursing, and public health. They have shaped the University, too, drawing on partnerships with Seoul National University, the Korea Foundation, and others; supporting academic exchange programs; and, backing the establishment of Pitt’s Korean Heritage Room. These alumni are part of the colossal effort that turned the world’s second-poorest nation into the 11th largest economy—in just three and a half decades.

Writer Ervin Dyer traveled to South Korea to meet just some of Pitt’s notable South Korean alumni and hear their extraordinary. Read below about these architects of modern South Korea who came to Pitt between the 1960s and early ’90s and harnessed their educations for lives of impact:

Sang-joo Lee (EDUC ’71G): Captain of culture and education

Shin-Bok Kim (GSPIA ’72, EDUC ’73G): University leader

Seung Wook Lee (GSPH ’79, ’82): Biostatistics pioneer

Hyun Kyung Moon (GSPH ’86): Trailblazing researcher

Ohjoon Kwon (ENGR ’85G): Global steel industry giant

Kyungbae Chung (A&S ’86G): Social welfare innovator

Gio-bin Lim (ENGR ’89): Engineer and industry influencer

Keun Namkoong (GSPIA ’89): Public service groundbreaker

Namgi Park (EDUC ’93G): Educator of educators

Sang-joo Lee (EDUC ’71G)

Captain of culture and education

At Pitt: He embraced interdisciplinary study and earned a PhD at the School of Education.

In South Korea: Lee served as deputy prime minister of education; held the position of president at four different universities; chaired high-level negotiations that led to the founding of South Korea’s professional baseball league; helped lift the Korean Symphony Orchestra to international acclaim; and was awarded South Korea’s first-class Medal of Honor.

When Sang-joo Lee began to plan for college at the age of 17, the world—and his world—was changing. It was 1953. His high school years were bright. The tall, slender teenager played basketball and the French horn, and wrote poems in the school’s literary club. He was also a good dancer, whose grace and agility impressed his physical education teachers. But for his country, those years were difficult. The Korean War raged from 1950 to 1953, turning farmland into killing fields and leaving an estimated 1 million South Koreans dead, wounded, or missing.

When Sang-joo Lee began to plan for college at the age of 17, the world—and his world—was changing. It was 1953. His high school years were bright. The tall, slender teenager played basketball and the French horn, and wrote poems in the school’s literary club. He was also a good dancer, whose grace and agility impressed his physical education teachers. But for his country, those years were difficult. The Korean War raged from 1950 to 1953, turning farmland into killing fields and leaving an estimated 1 million South Koreans dead, wounded, or missing.

Lee grew up and went to high school in Busan, a city perched on the Korea Strait. Like most Korean families, the Lees were financially destabilized by the war and its aftermath. The hardships made escaping poverty a key goal, and Lee set his sights on higher education.

He went to Seoul National University (SNU), where he studied educational administration. He finished in 1960 and then served his compulsory military service and taught speech and communication with the Korea Air Force Academy.

After four years, he went back to SNU, and earned a master’s degree in educational psychology in 1966. He approached his studies as if driven by a fever. A professor noticed his passion, and recommended that he apply to study at the University of Pittsburgh.

Lee arrived at Pitt in the fall of 1967. He was 30.

He became one of the first SNU students enrolled in Pitt’s School of Education’s emerging International and Development Education Program. The exchange initiative was designed to advance South Korea’s mid-career professionals and leverage Pitt’s study of Asia. He was supported by three scholarships: one from Gulf Oil, which paid his tuition; another from the Asia Foundation, which paid living expenses; and a Fulbright Scholarship, which paid for his airfare.

At Pitt, he earned a PhD in the School of Education. But his study allowed him to take classes in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (GSPIA) and other social science departments.

In an age of Beatlemania and Afros, Lee was a conservative student with a sensible haircut who always wore a suit jacket to class. But he says his time at Pitt exposed him to new worlds. The Pittsburgh Foreign Visitors Council gave him tickets to Pirates’ games and the symphony. He witnessed the Civil Rights Movement, the moon landing, and the social unrest after the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy.

“I saw people and studied ideas very different than what I was oriented to,” he says. “I became a more open person.”

Lee graduated in 1971. The development lessons he acquired in the classroom, coupled with informal discussions with other students of political science and economics over pizza and Iron City Beer, put a whole new life in front of him.

He returned to South Korea reborn with new ideas and new ambitions. He built a varied and distinguished career, serving at high levels in the national government, directing two different research institutions, and becoming president of four different universities. In addition to his civic and academic leadership roles, he lectured and found time to author two memoirs. He was eventually awarded one of the government's highest distinctions in South Korea, a first-class medal of honor for public service.

His years in Pittsburgh remained a strong influence. His beloved student pastimes of sports and music seeded the foundation for his work as the South Korean government’s senior secretary of education and culture to the president. In 1980, he began collaborating with businesses to support South Korean baseball. The negotiations eventually gave birth to the professional Korea Baseball Organization in 1982 and, he says, would soon earn him the moniker “the Father of Korean Baseball.” Today, the baseball league, followed by millions, is one of the most popular sports in the nation.

Similarly, he built collaborations with the Korean Broadcasting System to boost the profile of the Korean Symphony Orchestra, helping to turn it into a much-heralded cultural institution.

“My goal,” he says, “was to link the government with private business and public relations. I thought it would strengthen the organizations inside and out.”

As a result of Lee’s vision, the orchestra increased its talent pool, and earned an international reputation.

Lee says that Pitt helped him to look the future in the face. He fostered national development based on interdisciplinary research, he became a cultural leader, and shaped educational policy that would help to provide more children with the same opportunities to succeed that he’d had.

Shin-Bok Kim (GSPIA ’72, EDUC ’73G)

University leader

At Pitt: Kim earned both a master’s in public and international affairs and a PhD in education—in just two and a half years.

In South Korea: He championed educational reform and excellence, becoming the first at Seoul National University to hold the positions of provost and executive vice president; and, as the government’s vice minister of education, he reorganized vocational colleges and collaborated to hire more teachers and build more classrooms.

When he arrived at the University of Pittsburgh, Shin-Bok Kim felt like he didn’t have even a minute to waste. It was 1971, the year the Pirates won the baseball World Series, but the studious young man didn’t attend a single game. He had come all the way from South Korea to earn a master’s degree from the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (GSPIA) and he aimed to get the most he could from the two-year program.

When he arrived at the University of Pittsburgh, Shin-Bok Kim felt like he didn’t have even a minute to waste. It was 1971, the year the Pirates won the baseball World Series, but the studious young man didn’t attend a single game. He had come all the way from South Korea to earn a master’s degree from the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (GSPIA) and he aimed to get the most he could from the two-year program.

At Pitt, Kim did what he had done while in college back home—he studied, studied, and then studied more, sometimes for 14 hours a day. When new challenges emerged, he faced them head-on. Eager to participate in classes, for instance, the scholar, who was still working to perfect his English, spent his nights carefully scripting and memorizing his comments so that he could clearly recite them the next day.

He threw himself into studying the role of education in economic development, the subject he says that most fascinated him, and savored time spent with fellow students discussing ideas and collaborating across disciplines. As his understandings of his area of study broadened, Kim decided to simultaneously pursue an additional graduate degree at Pitt, this one a PhD in education.

“I had ambition,” Kim recalls.

He was used to hard work and determination long before arriving at Pitt. In South Korea, Kim grew up the son of a principal who served a school in a small island farming community. The Korean War, however, devastated the island’s resources, and nearly forced the school to close. The situation made Kim’s father even more determined to give his son the opportunity for a better education. In 1957, when he was 12 years old, Kim was sent to the mainland to attend school in Mokpo, a city by the Yellow Sea.

For six years, Kim lived in a room by himself in a private dormitory. His father visited every month, bringing with him high expectations for the boy’s academic success.

Kim wanted to make his father proud. He was a high-achieving student, and his grades earned him a place at Seoul National University (SNU). He left Mokpo and moved 200 miles to the capital city to study education, his tuition exempted, he says, by the government, he says, as part of a program to expand the country’s teaching corps.

At the time, Kim dreamed he would finish college, return to Mokpo, and become the superintendent of a local school district. He thought he would be content to advance a few professional levels above his father’s educational career.

Then, Pitt called.

A dean at SNU noticed Kim’s exceptional work as a student and recommended that he study at Pitt, a school with which the South Korean university had recently launched a cooperative partnership in the areas of public administration, education, and the social sciences. With a scholarship from the United States Agency for International Development, Kim boarded his first international flight and came to Pittsburgh.

Just two and a half years later, Kim earned both a master’s degree from GSPIA and a doctorate from the School of Education. It was an impressive feat, but merely a prelude to the accomplishments still to come.

Returning home to South Korea, Kim embarked on an influential and wide-ranging career in education. He worked with the Korean Educational Development Institute and the Presidential Commission on Education Reform, and served as a vice minister of Education and Human Resource Development for South Korea’s national government. He focused on educational reform and developed proposals and partnerships that led to a rise in vocational colleges, a reduction in public school class sizes, the hiring of more teachers, the strengthening of teacher-training requirements, and the implementation of technology and TV/radio broadcasts to tutor rural students.

Kim also spent 35 years at SNU, where, at one point, he was executive vice president and provost, the only person in the school’s history to hold both positions for four years. His responsibilities included student affairs, facilities, faculty, and personnel.

Kim is retired today—lecturing and serving on the board of Gachon University. Looking back at the role his education played in his long and luminous career, he says, “My time at Pitt made me a leader.”

Amid a lifetime of hard work and determination, those whirlwind two and half years of intense study and exploration in Pittsburgh helped Kim deliver new opportunities to students across South Korea.

Seung Wook Lee (GSPH ’79, ’82)

Biostatistics pioneer

At Pitt: He earned a public health doctorate in biostatistics from the Graduate School of Public Health.

In South Korea: Lee served as dean of the public health department at Seoul National University; shaped national health policy by amassing pioneering vital statistics on health, education, and public welfare; was awarded a National Medal, one of the South Korean government’s highest honors; and, in 2017, was named an “outstanding figure in public health” by the Korea Public Health Association.

Hyun Kyung Moon (GSPH ’86)

Trailblazing researcher

At Pitt: Moon earned a PhD in public health with a focus on nutrition from the Graduate School of Public Health.

In South Korea: She forged a trailblazing career as a researcher, professor, author, and women’s leadership advocate; served as president of the Korean Dietetic Association; wrote one of South Korea’s first nutritional policy papers, helping to drive government policies about food and nutrition; and was awarded a National Medal, one of the South Korean government’s highest honors.

Today, husband and wife Seung Wook Lee and Hyun Kyung Moon are each independently valuable contributors to South Korea’s public health sphere. Their paths toward success intertwined as young graduate students and began to blossom when each made a stop at the University of Pittsburgh.

Today, husband and wife Seung Wook Lee and Hyun Kyung Moon are each independently valuable contributors to South Korea’s public health sphere. Their paths toward success intertwined as young graduate students and began to blossom when each made a stop at the University of Pittsburgh.

Though Hyun Kyung Moon was born in the middle of the Korean War, she says her early years were not especially shadowed by her country’s strife. Her father, a war correspondent and later a professor, never talked to her about the war. She grew up with her family in Seoul enjoying summer vacations to the beach, small cakes for her birthday, and quiet time amid the lilies, golden bell, and wild roses in her grandmother’s garden.

Reading was a favorite pastime. “I was curious about life and I liked everything,” she recalls. Books, perhaps, gave her the appetite to reach beyond the traditional life of being a housewife. She dreamed of being a physician, a journalist, and a teacher.

After she graduated from one of the top high schools in Seoul, she attended Seoul National University (SNU). Moon’s family could not afford to send her to medical school to pursue her dream of becoming a doctor, so the young woman, undeterred, set her sights on a career in food and nutrition.

As a graduate student at SNU studying public health nutrition and working as a high school teacher, she met a shy young man, a fellow student, several years her senior. His name, she learned, was Seung Wook Lee, and by the time he met Moon, he had already re-made himself.

Lee was born in 1948 in Daejeon, the nation’s fifth-largest city. Because his father worked for one of the emerging electrical companies, Lee grew up in several small cities, as his father was often transferred to serve as an accountant at the developing branches. By 1961, when Lee was 13, the family was settled in Seoul.

He was a good, but introverted student who harbored a drive to better himself. By the time he reached SNU, for example, he had resolved to change his fear of public speaking. He became a reporter with his university magazine, an activity that forced him to talk with others and helped to open him up to the world.

He finished college with an advanced degree in veterinary medicine, but he soon wanted to do more than tend to animals. He became inspired by humanitarian philosophies and began to ask how he could help other people. Once again, he pushed himself forward.

Ultimately, Lee decided to study public health at SNU, a move that led him not only toward a career he felt passionate about, but also to the woman who would become his wife.

Lee and Moon married the same year he finished the public health graduate program.

Together, the couple embarked on their first big adventure: a journey to the U.S. city of Pittsburgh, where Lee was admitted to a doctorate program in biostatistics at the University of Pittsburgh’s Graduate School of Public Health.

“It was like a second life,” he says, “because we virtually started from nothing.”

The couple had little money and Lee still had much to learn about the English language and biostatistics. As he studied, his education funded through scholarships, Moon worked in minimum-wage positions to support the family. The experience was difficult, but they faced the challenges with tenacity. Lee, for example, would tape-record his classes so that he could listen to the professors’ lectures over and over again.

He finished a doctorate in public health with a focus on biostatistics in 1982, and for a year afterward, he conducted postdoctoral study in epidemiology at Pitt. When his work was done, he returned home to South Korea alone.

With Lee’s degrees secured, it was now Moon’s time to study. As her husband flew thousands of miles away, she remained in Pittsburgh to earn a Pitt PhD in Public Health with focuses on epidemiology and nutrition. Pregnant when she started the degree, she returned home to Korea to give birth to a daughter, but did not stay for long. The dedicated scholar soon returned to Pitt and full-time doctoral study.

For a young woman who grew up wanting to shatter glass ceilings, graduate school at Pitt was one of her first cracks at it. She cocooned herself in her studies.

“Now, I had a chance to get a degree from an American university,” she recalls. “To study hard was my choice. I was highly motivated. The new knowledge, the opening of my mind, was exciting.”

Moon remembers being quiet in classes but questioning her teachers afterward, and relying on kind-hearted classmates to help with translations. When not studying, she worked as a research assistant and teaching fellow. She graduated in June 1986, and one month later she was home.

The woman with the freshly minted Pitt PhD stepped back into a rapidly developing South Korea. New opportunities were becoming available to women. In a modernizing Seoul, Moon began her work life as head researcher at the government’s prestigious Korea Food Research Institute.

As her career blossomed, she presided over key professional nutritional societies, authored books on nutrition, and guided government-based projects to educate rural physicians on nutrition, which included surveys that focused on women, the elderly, and children. She continued much of that work until she retired recently as a full professor from Dankook University.

Moon’s work in nutritional epidemiology was a breakthrough. In an era when illnesses like diabetes and hypertension were on the rise, Moon’s studies linked diet to disease and helped to drive government policies that regulate food additives and safety. She was also responsible for building one of the nation’s first nutrition charts, a data system to help Koreans understand what to eat.

Her career’s ascension, coupled with her advocacy, helped pave the road for other women in her field.

“Everything I’ve done is possible because of Pitt,” she says. “It gave me the credentials to be in the room. To have a voice. It got me invited to the table. If they don’t invite you to the table, you can’t say what you have to say. Going to Pitt, made it easier for me to start to do something.”

After Lee left Pitt, he built a successful career that cut across teaching and public service, helping Korea as it emerged into a more modern age.

He served as a college professor of public health in South Korea and eventually became dean of the Graduate School of Public Health at Seoul National University. From there, he launched collaborations with schools of public health in Beijing and Tokyo that created visiting scholar partnerships to address “rising industrialization and smog as regional public health issues.” The collaborative work, Lee says, helped to influence policy regarding South Korea’s health care systems, health promotions, and environmental health measures.

But perhaps his most significant contributions came in the area of biostatistics. In the mid-1980s, he was one of only a few biostatisticians in South Korea and soon went to work with Statistics Korea, a government agency dedicated to the development and improvement of the collection of vital statistics.

There, Lee contributed to developing national indexes on how to gather data on birth and death rates. His work was particularly relevant in rural communities, where it proved necessary to for tracking and understanding high infant mortality. He would go on to strengthen the government’s biostatistics on health, social affairs, environment, education, and children’s health. His research gave the government the reliable information needed to shape better policy on health and human wellness.

He says Pitt helped to “open the doors” for him to have a distinguished career. He served as a visiting scientist with the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development with the U.S.’s National Institutes of Health. He was a visiting professor of public health at Curtin University of Technology in Australia. At Seoul National University, he served as dean, director of community health research, director of the institute of health and environment, and chair of the department of health services and sciences—all at the Graduate School of Public Health.

Lee and Moon were each awarded a National Medal, one of the government’s highest recognitions, for their excellent work and contributions to society.

In a span of 40 years, and through the aid of idea-expanding education, the bookish girl who looked beyond the horizon and the shy boy who dreamed of helping people had transformed not only their own lives, but also many of the lives of their fellow countrymen and women.

Ohjoon Kwon (ENGR ’85G)

Global steel industry giant

At Pitt: He studied the thermo-mechanical processing of steel and earned a PhD in materials science and engineering at the Swanson School of Engineering.

In South Korea: Kwon is CEO of POSCO, the world’s fifth-largest steel-making company. He steadily rose through the ranks of research, technology, and executive governance, guiding POSCO into a role as a major contributor to South Korea’s automotive, shipbuilding, and construction sectors; led the company’s research and development center and its European Union office in Germany; and, in 2016, was named one of the nation’s top scientists by the Korean Federation of Science and Technology Societies.

Growing up in the rural South Korean city of Yeongju, Ohjoon Kwon’s responsibilities at home included caring for the family’s electrical appliances. He took pride in the work. His mother, observing her son’s skill, recommended that he study engineering in college.

Growing up in the rural South Korean city of Yeongju, Ohjoon Kwon’s responsibilities at home included caring for the family’s electrical appliances. He took pride in the work. His mother, observing her son’s skill, recommended that he study engineering in college.

Kwon liked the idea. He was born in 1950, at the very cusp of the Korean War (his family was forced to flee the violence when he was an infant). Coming of age in a post-war nation had given him the drive to pursue work that might benefit the country’s continued development. But as the son of a father who owned a small lumber mill knew also he would have to work hard to earn his place in a university.

Like many South Korean families hoping to give their children the best future possible, Kwon’s parents sent him to Seoul to attend high school. At age 18, after months of intensive study to pass the entrance exam, he was accepted to Seoul National University (SNU). He had ambitions of studying mechanical engineering but, after reading about the establishment of a large South Korean steel firm, the student altered his focus. He decided to study metallurgical engineering with hopes of one day working in the steel industry.

Kwon graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1972. After he served his mandatory military duty, he found work in research and development for the defense industry. As a young engineer, he took a closer look at the global steel industry. He saw its continued emergence in South Korea and, wanting to learn more, set his sights on coming to the United States, then the center of the industry.

First, he earned a master’s degree in metallurgical engineering from the University of Windsor, in Ontario, Canada. Then, he applied to a doctorate program at the University of Pittsburgh, in the home city of U.S. Steel, the world’s largest steelmaker at the time.

Kwon was 32 when he arrived at Pitt with his wife and young son. While his wife, Chungsun Park (A&S ’87G), studied for a doctorate in sociology, he immersed himself in his doctoral studies in metallurgical engineering.

The engineer came to Pitt in part, he says, to study with Anthony J. DeArdo, a noted Pitt engineering professor who had expertise in both theory and practice. With the aid of DeArdo, Kwon was able to secure scholarships from the National Steel Corporation and the Brazilian company, CBMM. DeArdo, Kwon says, was also able to nurture his academic and professional growth.

“Working with Professor DeArdo,” says Kwon, “I was able to broaden my perspective. I was able to present research, exchange ideas with not just fellow engineers but also with businessmen in the industry.”

Kwon was a serious and committed graduate student, often working overnight in the labs to finish his experiments. He embraced the rigorous academic and research environment at Pitt. Absorbing new theories and using sophisticated equipment made him adaptive and open to new challenges, he says. It helped form the foundation of his professional philosophy that innovation should be welcomed in the steel industry. “I learned that a strong research and development environment is critical to enabling breakthroughs,” he says.

But he also enjoyed the social elements of life at Pitt, especially attending football and baseball games. He jumped at chances to participate in academic presentations and international conferences, which he saw as opportunities to practice his English, learn new scholarship, and cultivate a professional and intellectual network. Harnessing these cross-cultural and language skills prepared him for leading in a global society, he says.

He served as president of Pitt’s Korean Student Council, which helped him to meet business leaders who visited campus. As he neared the end of his doctoral work, Kwon was connected with a high-level executive from POSCO, South Korea’s steelworks giant. The executive was impressed with the young engineer and invited him to join the company—an invitation that would change his life.

In 1986, Kwon returned to South Korea and began a career at POSCO in research. Over the years, he ascended into the company’s leadership roles, serving as assistant director and then director of POSCO’s Research Institute of Industrial Science and Technology, and the company’s chief technical officer. In 2014, he was named chief executive officer.

Today, he is reshaping the global conglomerate into what he calls a “smart industry,” bringing innovation to the steel industry through artificial intelligence and automation. His leadership has been noted to have increased the quality of the company’s products, improved its financial structure, and nurtured new business growth.

Kwon says that what he learned at Pitt has helped advance his ideas on research and development, benefiting POSCO and South Korea, too. “Pitt,” he says, “was truly a turning point in my life.”

Kyungbae Chung (A&S ’86G)

Social welfare innovator

At Pitt: He earned a PhD in economics from the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences.

In South Korea: Chung revolutionized the social welfare network by developing a national pension plan using long-term projection modeling learned at Pitt; introduced productive welfare, an innovation that included housing, education, and self-help programs for the poor; and instituted health insurance and a national pension to cover all citizens.

Kyungbae Chung boarded the slow train to Seoul in the summer of 1958. Accompanied by his grandmother, a sister, and two brothers, he was leaving the small community within his hometown of Mokpo, saying goodbye to much of the neighbor-caring-for-neighbor customs he had loved growing up.

Kyungbae Chung boarded the slow train to Seoul in the summer of 1958. Accompanied by his grandmother, a sister, and two brothers, he was leaving the small community within his hometown of Mokpo, saying goodbye to much of the neighbor-caring-for-neighbor customs he had loved growing up.

The long trip lasted 10 hours. If he looked back, he was reminded of the villagers who had deposited in him the value of hard work and who, traumatized by war and living with very little, had leaned on each other for support.

The young man’s family was moving to the capital city to join his father, who had found work there as a tailor. But Chung was drawn there for another reason: he had been admitted to Seoul National University (SNU) to study English education. He was no longer looking back; he was looking forward. And though the rapidly expanding city of Seoul was 200 miles away from Mokpo, the distance between the old ways and the new frontiers that awaited him was immeasurable.

Chung earned a bachelor’s degree from SNU, and then pursued a master’s degree in public administration while serving in the military. But along the way, an internship with the Economic Planning Board awakened a curiosity in economics. He says that his experience growing up in a war-ravaged nation made him especially interested in the subject.

When he finished at SNU, he worked as a teacher and economist, but not long afterward, he would once more pull away from much of what he knew. This time, he would make the leap over an ocean.

Chung first arrived in the United States in 1973. He was 35, married with two young children, and a new student at Wayne State University in Detroit, Mich. In just two years, he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in economics and went to work for the retail giant, Kresge. But the economist wanted to learn more.

He heard of the stimulating research at Pitt and, in 1982, after earning admission, he headed to campus to earn a PhD in economics.

In Oakland, he found a welcoming environment and a circle of top scholars. Economist and professor Marina Whitman, the daughter of noted mathematician, physicist, and computer scientist John von Neumann, the noted mathematician, physicist, and computer scientist, was there. Her father was a friend of Einstein, whom, he recalls, she called Uncle Albert. Pitt’s economics professors, including Jim Kenkel, Mark Perlman, and Alvin Roth, who later won a Nobel Prize in economics, opened Chung’s eyes to the use of advanced mathematical optimization tools in economics.

“These people supported my imagination, my theories, my new ideas,” says Chung, who studied progressive and advanced theories of economics. Even in the 1980s, he says, people at Pitt “were studying theories of artificial intelligence, automatic controlled cars. The environment fit with me.”

In 1986, Chung carried these ideas and imaginations home when he returned to South Korea. He taught welfare economics and financing at SNU and researched social security for the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. By 1988, he was part of a highly respected team tasked with considering a national pension plan and exploring how it could it be used to address the divide between poor and rich, capitalist and worker.

Chung says he relied upon skills learned at Pitt to construct a computer and prediction model that perfected the team’s ideas. His approach modernized the South Korean welfare state and advanced a national pension, and health insurance, employment insurance, and more.

The model was adopted by the government in 1998. More than 50 million people use the system.

Later, Chung took his ideas even further when he introduced the system of Productive Welfare to South Korea. Its philosophy is rooted in the idea that welfare should encourage work and be useful in moving society forward. It consists of national pension and health care systems, social aid and self-help to the poor, and long-term care for the elderly.

The government adopted the Productive Welfare plan a few short months after it was introduced. Its innovative concepts were a return to the traditional values of caring for family and community, values Chung grew up surrounded by in Mokpo.

The economist says that Pitt helped him share with his whole country his belief in “community caring for community.” His studies gave him the tools to help others in new and meaningful ways.

“Without Pitt,” he says, “I would not be where I am today. I’m a Pitt product.”

Gio-bin Lim (ENGR ’89G)

Engineer and industry influencer

At Pitt: He earned a PhD in chemical engineering from the Swanson School of Engineering.

In South Korea: Lim is a professor of engineering at the University of Suwon and a collaborator with government and private industry, particularly in the technology and pharmaceutical sectors. His work advances research, economic development, and commercialization, helping to marshal billions in research and tech funding to support innovation and advancement.

The little boy growing up in Seoul loved to discover how things work. He would take apart watches, disassembling and reassembling their delicate machinery until they whirred back to life. As he got older, the curious Gio-bin Lim thought his interests might lead to a career in engineering.

The little boy growing up in Seoul loved to discover how things work. He would take apart watches, disassembling and reassembling their delicate machinery until they whirred back to life. As he got older, the curious Gio-bin Lim thought his interests might lead to a career in engineering.

“Our country did not have enough chemical engineers, and petroleum was a growing field,” says Lim, who initially thought he’d go into oil and gas research and join a new generation of South Korean students emerging with fresh ideas and possibilities.

In 1974, Lim went off to Yonsei University in Seoul ready to learn how he might prepare to advance his nation and the world. “I was the student who didn’t like to memorize. I loved hands-on and not history,” he recalls. “I was going to follow the path of something hands-on.”

He majored in chemical engineering. Yet, a seed had been planted in him years before, when he was growing up the inquisitive son of a small businessman. He came to believe that commerce intertwined with research and innovation could be transformative.

Lim’s father sold piping, did printing, and worked in photography. He taught his son about selling and product development, lessons that followed the boy to college. As Lim dove in to the academic investigations taking place at his university, he became increasingly intrigued by the ways that classroom research, when partnered with business, could develop products that help people heal, work more efficiently, and live better lives.

“I’m an engineer,” he says, looking back at his school days, “but I’m always thinking about life and how you design products that matter in everyday life.” Many researchers don’t look into that dynamic element, he adds, “so the gap between knowledge and commercialization is like Death Valley.”

Lim’s next steps would be to help narrow that gap. He was a junior in college when he decided he wanted to study outside of South Korea. After graduating with a master’s degree in chemical engineering, he applied to Pitt as a doctoral student in the Swanson School of Engineering. Pittsburgh’s industrial past reminded him of Korea.

Gerald D. Holder, now dean of the Swanson School, became Lim’s professor and mentor. They met once a week during Lim’s dissertation research on supercritical fluids, or fluids that have properties between those of a gas and a liquid.

But in Pittsburgh, Lim gained more than just scientific knowledge. Charismatic and outgoing, he served as president of Pitt’s Korean Student Association. The leadership role gave him practice in the techniques of person-to-person business. He learned how to network, he says, and how to build bridges across groups for the sake of common goals.

After earning a doctorate in 1989, Lim conducted post-doctoral study at Cornell University and at Princeton, where his research on supercritical fluids and nasal spray was licensed by a pharmaceutical company and considered for product development. By the time he returned to South Korea, he was filled with innovative ideas that blended research with business to bring engineering advancements to the public.

Today, Lim is a professor of engineering at the University of Suwon outside of Seoul, where he has built relationships with the government, private industry, pharmaceuticals, and technology enterprises to further collaboration that promotes research, commercialization, and economic development.

He’s worked with the government’s Ministry of Science and Technology, and its Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy; the Korea Biotech R&D Group; and the Korean Society of for Biotechnology and Bioengineering, a group of 7,000 professors and researchers seeding next-generation productivity and innovation. Through his leadership, he marshaled researchers in biotechnology, bio chips, pharmaceuticals, and engineering, and drew government support and other grants to oversee nearly a billion dollars in funding to advance university research and commercial collaboration.

Standing on a sturdy educational foundation, Lim’s efforts have brought advancements to research and development on drug delivery systems, to organ xenotransplantation, and in moving biopharmaceutical tests from animals to humans. He has overseen breakthroughs in allergy screening, and as well as in a vaccine to address cancer in the womb. In the past few years, he has chosen to focus on the new industries of bio-, nano-, design, and conversion technology.

“The ideas I learned about engineering and applying research, and building synergy to do something for human life, came to me at Pitt,” says Lim. “We need to turn ideas into products, pharmaceuticals, and medical devices to do something for human life.”

And that’s just what he’s doing.

Keun Namkoong (GSPIA ’89)

Public service groundbreaker

At Pitt: Namkoong earned a PhD in public and international affairs from GSPIA.

In South Korea: He advocated for and instituted changes to how government administrators use research to build better policy; wrote two widely used books on research methods and public policy; and helped transform Seoul National University of Science and Technology into a globally respected research institution as the school’s president.

By 1954, South Korea had reached a turning point in its history. The war’s fighting had ceased, and thousands were migrating to the cities, looking to outrun the deprivation, destruction, and pestilence wrought by the conflict. They wanted hope.

By 1954, South Korea had reached a turning point in its history. The war’s fighting had ceased, and thousands were migrating to the cities, looking to outrun the deprivation, destruction, and pestilence wrought by the conflict. They wanted hope.

At this moment, a mother in a countryside village about 200 miles from Seoul bore her first son.

Keun Namkoong was the fourth of her eight children. The boy’s father was a teacher and later a principal at a small elementary school. The father noticed that the world was changing and encouraged his children to think ahead. He told his son to go to law school to be a judge.

“My father saw that agrarian people who were rich had lives that were collapsing after the war,” says Namkoong. “He saw that farming, the old way of life, was changing and that education would be the way to advance in society.”

Namkoong grew to be an excellent student. In the spring of 1972, he left for Seoul National University (SNU), where he studied political science. Campus life, he says, was very liberal, and he enjoyed the freedom of academic exploration. Law was not for him, he decided. Instead, Namkoong studied social science and government, earning a master’s in public administration, with top honors, in 1978.

He pursued a career as a public servant, and then became a full-time lecturer of political science and public administration at a military academy while completing his compulsory military service.

Shortly afterward, Namkoong began to teach at a university south of Seoul, while keeping an eye out for opportunities to study abroad. He remembers, in 1984, being elated to receive a letter of congratulations from the University of Pittsburgh’s Graduate School of Public and International Affairs. He knew of GSPIA. He says it had a reputation for elevating South Korean public administration staff and claimed some well-known alumni who worked as professors in South Korea. So, when the offer from Pitt arrived, he accepted it immediately—again, guided by his father’s philosophy.

“My father always said the place where you’re born is not the place where you have to live. The encouragement was always to move forward. I did not hesitate to go to Pittsburgh because it meant I could go to a ‘rising place.’”

He knew that he could “rise” at Pitt because the study and training would be an opportunity to learn about the broader world.

“To not go was not an option,” he says.

Namkoong came to Pitt with his wife in the summer of 1985. He was 31. He approached his graduate studies just as he had his earlier education: with discipline. He would read all night, catch naps in the early morning, and then head to class. He bonded with international classmates—from China, Taiwan, and Saudi Arabia.

He earned top marks on his way to his doctorate in public affairs. His dissertation—a cross national study on public health policies and programs—earned national recognition. He worked with professors whom he calls innovators in public policy: Louise Comfort, William Dunn, and Guy Peters. He strengthened his skills in statistical research. He was awed by the amount of public and historical records in Hillman Library and inspired to improve his own nation’s library resources and documents.

When he returned home in 1989, South Korea’s economy, infrastructure development, and education were on the upswing. Namkoong’s work would contribute to this progress. He wrote two books on research methods and public policy that were widely used by students and South Korean public service officials. The books emphasize evidence-based research and policy making, both concepts and practices he learned at Pitt. His work was recognized by the prestigious Korean Association for Public Administration, which honored him with its Excellent Book Award in 1999.

He built an impressive career in educational leadership. As president of Seoul National University of Science and Technology, he transformed the school from a teaching university into a highly esteemed research institution, competitive in the fields of science, engineering, and technology.

Namkoong is now back in the classroom, teaching administration, but what he learned on the Oakland campus, he says, he used to shape a new generation of critical scholars and civil servants who practiced reason and analysis to better society. His expertise and high-level work paved the way for a more modern and efficient government—all because he followed his passion and his father’s advice to rise.

Namgi Park (EDUC ’93G)

Educator of educators

At Pitt: Park earned a PhD in education policy with a focus on comparative education.

In South Korea: He built a dynamic career in teaching, researching, and writing; became the youngest president of Gwangju National University of Education; chaired one of the nation’s largest collaboratives of educators; and is an author credited with influencing progressive teacher reform and a change to the culture of education in Korea.

The little boy was leaving Gumsan, a town so rural in 1967 that it had no cars. That morning, he and his father, a rice farmer, walked an hour to the nearest bus stop, where the 7-year-old boarded a bus alone. He carried a bag of fruit and boiled eggs to sustain him over the two-and-a-half-hour trek to the town of Gwangju, but the bus was so packed that there was no room to eat. He had to stand, pressed against the strangers traveling to make new lives in the city.

The little boy was leaving Gumsan, a town so rural in 1967 that it had no cars. That morning, he and his father, a rice farmer, walked an hour to the nearest bus stop, where the 7-year-old boarded a bus alone. He carried a bag of fruit and boiled eggs to sustain him over the two-and-a-half-hour trek to the town of Gwangju, but the bus was so packed that there was no room to eat. He had to stand, pressed against the strangers traveling to make new lives in the city.

When Namgi Park arrived in Gwangju, he joined his 12-year-old brother. They were there to attend school—a privilege, but one that came at a cost.

It was a threadbare life. The boys shared a tiny, bare room in a boardinghouse, where monthly rent was only $2 and the brothers had to warm themselves and cook by heating bricks of coal.

To rise up, Park determined that he would work hard and “make his life of nothing into something.” He studied day and night. Little outside of academics entered his world.

In his new city, the kindness of teachers—a few of them American Peace Corps volunteers—helped him endure the separation from his parents. They also planted the seed of an idea that one day he could come study in the United States. It was an improbable dream, but Park’s early success in a city school put before him possibilities that would have been unimaginable had he stayed on the rice farm. One day at a time, he stepped toward a different life.

When it became time for college, Park’s first plan was to become a lawyer, but he could not afford the expense of law school. Instead, he headed north, 160 miles, to Seoul National University (SNU), and he majored in education through a program that provided almost free tuition to those who qualified.

He fell in love with education and the chance to shape young minds and earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in education from at SNU. He took his first job doing research at the Korean Council for University Education. Park enjoyed the work, but the dream of going abroad planted by the Peace Corps volunteers nudged at him.

Then, in the summer of 1989, fortune favored him: a supervisor was unable to attend a conference in Washington, D.C., and tapped Park to attend. In the United States, he met up with a friend who was studying at the University of Pittsburgh. The friend invited Park to visit the campus and meet John Weidman, a professor in Pitt’s School of Education. Weidman, impressed with the young researcher, eventually offered him a research assistantship at Pitt.

A few months later, in the fall of 1989, Park arrived in Oakland. He was 29 and had nothing but two suitcases: One for clothes, the other for books. His wife and baby girl joined him six months later, and he settled into what he calls “the paradise” of campus life.

He enjoyed the free-flowing intellectual discussion, the interaction with professors, and the surge of energy he felt being in bustling, cosmopolitan Oakland. It was where he was able to do what he knew how to do: study day and night.

Park ultimately earned a Pitt PhD in education policy with a focus on comparative education. His Pitt studies, he says, opened the doors to international friendships, stronger leadership skills, and an understanding of education systems across the world. He left Pennsylvania feeling empowered and deeply connected to Pitt. Three times after graduating, he returned to the University as a visiting scholar. He would even later collaborate with Weidman, one of his closest advisors, to co-author a text on higher education in Korea.

Equipped with new ideas and analytical skills from Pitt, Park plowed a path that influenced and changed the South Korean education system. First, he built his own career: teaching, researching, and, eventually, becoming the youngest president of Gwangju National University of Education. He has lectured across South Korea and authored more than 400 articles. He also served as chair of the prominent University Presidents’ Group, a consortium that works with university leaders across South Korea. With this group, Park was able to broadly share his views of how to improve teaching in South Korea.

As a result of his advocacy, the South Korean government prohibited corporal punishment in schools, adjusted policies in university admissions, and pushed for reforms that focused on children’s abilities without regard to resources of the parents.

“You cannot change the education system through revolution,” he said. “It must be done through the heart and soul of individuals. To change the students, you have to change the teacher.”

The little boy who boarded the bus alone was now a national thought-leader, giving teachers the tools to put other South Korean children on the path to their highest aspirations.

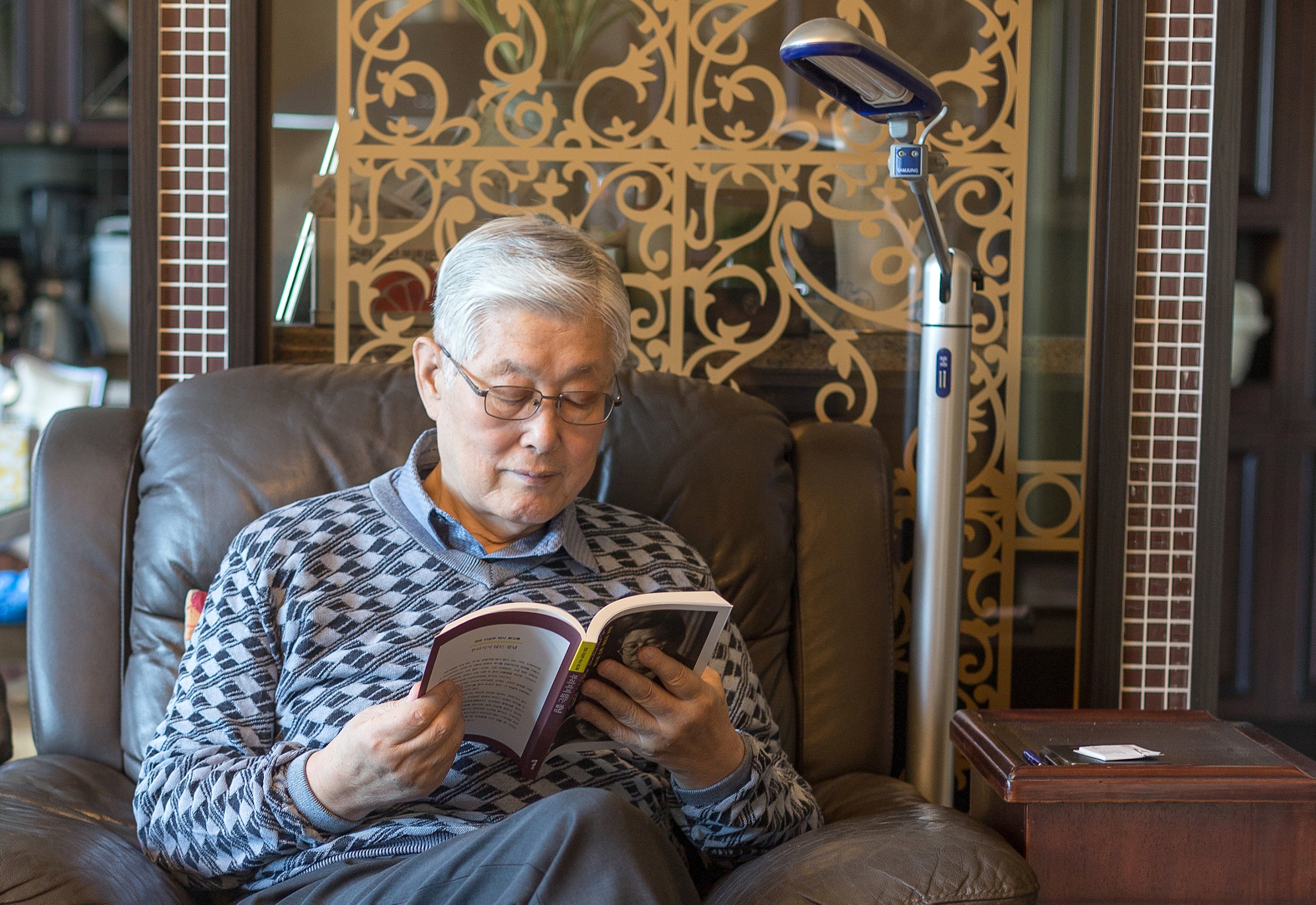

Opening image: Byong Hyon Kwon