A woman with visual impairment struggles to get through a narrow passage between chairs. She reaches out an arm, attempting to maneuver her way around tables in a crowded restaurant setting.

Looking on impatiently, a waiter says, “Ma’am, you’re disturbing the other guests.”

For the diner trying to navigate her path, the embarrassment and frustration are palpable.

This scene unfolds not in the dining room of a fancy restaurant, but in the second-floor ballroom of Pitt’s O’Hara Student Center, where tables and chairs are set up in an interactive exhibit called the Disability Diner. The restaurant patron is, in fact, an undergraduate student wearing goggles that block her vision. Several fellow diners, also students, wear noise-canceling headphones that simulate deafness. Another tries to reach the table in a wheelchair.

Designed by members of Pitt’s Students for Disability Advocacy, the Disability Diner was one of eight interactive exhibits or “rooms” featured in “Boxes and Walls,” a two-day event last spring sponsored by Pitt’s Division of Student Affairs. Other rooms focused on issues including food insecurity, anti-Semitism, and awareness of sexual assault.

The event’s purpose was to present students with situations and circumstances they may not encounter in their everyday lives, encouraging them to think about—and even feel for themselves—others’ experiences.

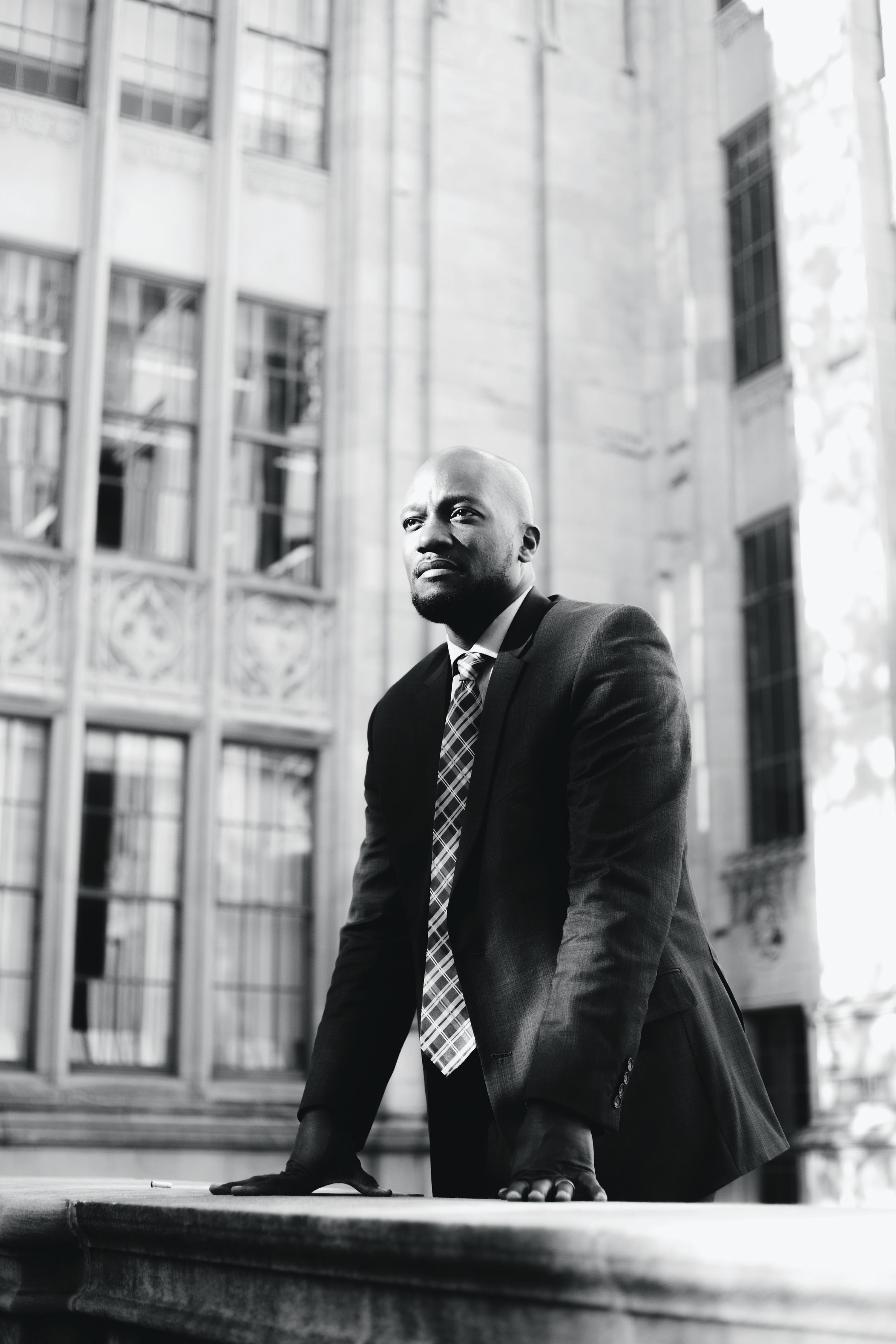

“The work and importance of community starts with each of us,” says Kenyon Bonner, who leads Student Affairs as vice provost and dean of students.

For much of his professional career, Bonner has been bringing students together, helping them find their way. He knows, too, that it’s equally important for them to support each other. It’s a philosophy he calls “lift as you climb,” premised on his belief that as students learn and grow, they have the responsibility to help others excel and grow as well.

That outlook took root in him long ago in a tough neighborhood in Cleveland where he grew up, the eldest of three siblings. In the 1970s, shifting economies began rusting out many industrial centers, including Cleveland. As jobs and hope withered, crime and gangs sprouted. The Bonner family’s home was broken into twice, and a 5-year-old Kenyon saw a man shot to death. His social worker father, Robert, and stay-at-home mom, Linda, worked hard so their children would see the world of opportunities that existed beyond the corner of 112th and Benham.

“We wanted our children to know that people do bad things, but you don’t have to be one of them,” recalls Mrs. Bonner about those years. Each night as her son went to bed, she read him a Bible verse. A favorite was Proverbs 22:6 “Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old, he will not depart from it.”

No matter the darkness outside the house, Kenyon Bonner would know the sunshine of promise. His parents believed education was a pathway to promise, and they sent him to a school district in his grandparents’ neighborhood, where the streets were safer, the instruction stronger. Through his parents, he also became immersed in the social networks of people helping people. His mom carried him to city council sessions as she petitioned for neighborhood improvements. He went with his union-officer father to meetings at Union Hall #1746 with the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees. He visited the Cayuhoga Department of Human Services, where he saw his father providing for people who needed food and shelter.

And, he had role models. James Collins supervised his father, and the Tuskegee University graduate treated the younger Bonner like a grandson. He took him to Cavaliers basketball games and drove him to basketball camp when the Bonners’ car wouldn’t run.

All of what Bonner saw taught him that “you don’t get through life without the help of other people.”

Today, Bonner has responsibility for helping some 18,000 undergraduates on the Pittsburgh campus. Bonner’s skills are particularly important as students navigate the terrain of adult life. And, as Pitt celebrates this academic year around the theme of diversity, he has a prime opportunity to share his philosophy: Help those around you to excel and grow—listening to, learning from, and respecting others who have dissimilar, even conflicting perspectives.

Today, Bonner has responsibility for helping some 18,000 undergraduates on the Pittsburgh campus. Bonner’s skills are particularly important as students navigate the terrain of adult life. And, as Pitt celebrates this academic year around the theme of diversity, he has a prime opportunity to share his philosophy: Help those around you to excel and grow—listening to, learning from, and respecting others who have dissimilar, even conflicting perspectives.

Those familiar with Bonner often see this principle in action. Around campus, he’s known for the way he easily glides into the daily orbit of students. He often sits at the back in meetings, listening to their suggestions to improve campus life. Afterward, he approaches those who expressed their views, invites them to chat, and encourages them to share their perspectives by joining a committee or panel to move their ideas forward.

Bonner arrived at Pitt in January 2004 from Kent State University, where he earned a master’s of education degree in rehabilitation counseling.

“I took counseling and enjoyed it,” he says, “but I became more excited about wanting to do the work that prevented kids from needing counseling.” That’s how he got into student affairs. At Pitt, he began as associate director in the Office of Residence Life, and others quickly noticed his skills with collaboration, counseling, and outreach to parents and students. He was promoted to director of the Office of Student Life, rose to associate dean and director of student life, and then served as interim dean of students for a year until his promotion last March.

Bonner was also given the leadership role with RISE, a Pitt program that prepares students not only for graduation but also for greater opportunities and rewarding lives. The innovative program mentors underrepresented students on their path to success.

In the early 1990s, as an undergraduate at Washington and Jefferson College in Washington, Pa., Bonner initially struggled with self-doubt and alienation. He was one of about 40 African American students on the rural campus of 1,200. There were no Black faculty. He initially wondered if he had made the right decision. The transition from urban Cleveland to the two-centuries-old W&J campus was a shock. Bonner had to confront differences of race, class, and culture. He dedicated himself to studying and getting to know his classmates. And, in time, he soared.

At Pitt, RISE is a program that helps students adjust to university life and rise to success, whether they come from the lawns of suburbia or the corners of urban America. It’s a space where the big campus becomes a small community.

RISE students use their individual skills to strengthen each other. If some excel in math, they’re expected to tutor algebra for others needing math help. If a RISE student is down, others are expected to offer a pep talk. RISE participants also mentor high school students and design community service projects.

Something else happens at RISE, too. Bonner’s quiet confidence and his ability to relate and speak comfortably to students’ concerns draws them in. Particularly, young African American men who, when they see the 6 foot 6 inch tall Bonner glide into a room with his dark suit, broad shoulders, and mile-long list of accomplishments, also see a vision of what they can achieve.

In 2009, KaHill Liddell walked into RISE. He was a solid student from a good school in Washington, D.C. and he was trying to find community at Pitt. He found it in the study sessions designed by Bonner, where another RISE student sat with Liddell to review his science lessons. He earned a Pitt undergraduate degree in health services in 2013 and was ready to pursue his highest goals, but also to pour himself into helping others. Today he is a lieutenant in the U.S. Navy, soon to set sail to Pearl Harbor where he will serve as a heath care administrator at a hospital in Hawaii.

Liddell credits his success to the “open door” relationship he had with Bonner, who would often initiate conversations on academics, social life, and leadership. “He definitely kept my head on,” says the Pitt graduate. And he’s one of many who have benefited from Bonner’s presence on campus and in their lives.

Bonner’s philosophy of lift as you climb is threaded throughout the fabric of all his chief priorities guiding the student experience on campus. He oversees nearly 200 staff members and coordinates programs and services to address the holistic needs of students. His reports include the Office of Student Life, University Counseling Center, Student Health Service, and Disability Resources and Services.

With the 2016-17 Year of Diversity, he is encouraging his staff and students to try new ideas. Already, they’ve taken a Civil Rights trip to the South and blogged along the way. They’ve created “Boxes and Walls,” and there are 100+ events throughout this academic year—many organized by students—to explore the theme of diversity.

With Title IX and the University’s commitment to zero instances of sexual assault, Bonner is working with student groups as they form programming to talk about issues of consent. He’s also continuing the effort to eliminate the stigma of mental illness and depression on campus, including more psychologists available to care for students at the counseling center and a student mental health task force on awareness and treatment.

On a personal level, Bonner is still climbing. One weekend a month, he boards the train and travels 16 hours round-trip to the University of Pennsylvania, where he is earning a doctorate in higher education management.

He’s still lifting, too. During Pitt’s orientation week in the fall, Bonner introduced a workshop on diversity and inclusion to 4,000 new students at the Petersen Events Center. It was an exercise designed to plant the seeds of acceptance and engagement in students during their time at Pitt and beyond: to use their heads, to think critically, to be curious; but also to use their hearts—to have empathy and grace for others who think differently.

He wants all students to know that “they are people privileged to receive a higher education,” and he wants them “to use their education to help make the community and the world a better place.”

It’s a universal formula for how to lift as you climb.

Opening image: Kenyon Bonner

This article appeared in the Winter 2017 issue of Pitt Magazine.